On biographing an ordinary life

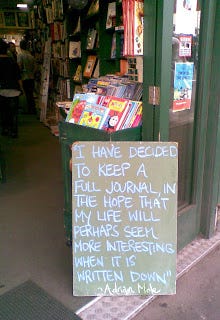

So I am back, and feeling like I should begin again with profound reflections on times past and goodly resolutions for the future. Instead I have a quote. I received Kiss and Tell by Alain de Botton for Christmas, and my confession is that I very much enjoyed it. It’s a novel, of sorts, but one in which de Botton writes a pseudo-biography of an ordinary life. The preface, from which I have quoted below, sucked me in. Interestingly, the book was written in 1995, before the advent of facebook and twitter, and before the prevalence of blogs, and it’s curious to think on how many are now seemingly engaged in biographing their own life (and how many are reading it) – and why.

Being a person who errs on the side of reserve, and so doesn’t tend to naturally probe too much into the swampy areas of others lives (not because I am not interested, but more because I don’t wish to be nosey), I have learnt something in recent years to combat this, which is that most people will actually read the probing as caring, and that there is something very compelling in someone taking an interest in the details and history of your life (possibly more compelling for single people, who must accept the reality that no-one is actually all that interested in their minutiae and history). But we all know that there are dangers that run both ways in a sharing of lives, and often pain involved when others either don't appreciate our attempts or care for our own story, and as I have looked back on the past year and areas where I feel like I’ve made errors in this respect I appreciated Duncan's post on why it's wrong to be other-person centred.

But without further ado, here is the quote from Alain de Botton. It’s rather long, but it’s the last few paragraphs that I found most worth reading. As de Botton writes in a section I haven’t included, many are the times we fail to truly listen to others and silently yawn and wonder what we have planned for tomorrow while mini-biographies unfold in front of us.

One might of course rejoin that never before have so many people devoted so much time to the minutiae of others. The lives of poets and astronauts, generals and ministers, mountaineers and manufacturers all lie before us on the tables of elegant bookshops. They herald the mythic age prophesied by Andy Warhol where everyone would be famous [that is, biographed] for fifteen minutes.

Yet there has always been some complexity in the fulfillment of this noble Warholian wish [the fact that it would take no less than 1,711 centuries to give all those currently breathing fifteen minutes of attention].

And whatever the practical difficulties, in a sombre though unplanned Warholian parallel, the philosopher Cioran once wrote of the impossibility of one person being truly interested in another for longer that quarter of an hour [don’t scoff, try it and see]. And even Freud, who one might have expected to cherish hopes for human understanding and communication, told an interviewer at the end of his life that he really had nothing to complain about: ‘I have lived over seventy years. I had enough to eat. I enjoyed many things. Once or twice I met a human being who almost understood me. What more can I ask?’

Once or twice in a lifetime. What a solitary sum, though what haunting paucity, provoking us to doubt the depth of our relations with those we sentimentally call our friends.

... If, as Warhol had implied, there was going to be a traffic jam of 1,711 centuries simply to accommodate everyone living, there was something selfish in the way certain characters had persistently hogged the biographical field: Hitler, Buddy Holly, Napoleon, Verdi [he included Jesus here, but I am leaving him out as someone who warrants the attention], Stalin, Stendhal, Churchill, Balzac, Goethe, Marilyn Monroe, Caesar, W.H. Auden. It wasn’t hard to see why, for these figures had exercised enormous power, artistic or political, beneficial or not, over their fellow men and women. Their lives were what might lazily have been called larger than life, they expressed the outer limits of human possibility, something one might gasp at and be thrilled by on the morning commuter train.

However, on a closer look, it appeared that biographers were not primarily concerned with highlighting the difference between the great and mortals consigned to using public transport, but rather were keen to show how their charges had [despite conquering Russia, subduing the Indians, writing La Traviata and inventing the steam engine] been much the same as you and me. The pleasure of reading biographies arose in part from a reminder of flesh and blood in creatures one imagined to have been fashioned of sterner stuff; personality was of interest, the humanity which arose from a telling detail and history had airbrushed from its solemn portrait.

There was a thrill in learning that Napoleon [invincible Bonaparte whose body lay in glory beneath ten feet of marble in the gilded Invalides] had a fondness for grilled chicken and jacket potatoes. With his love of this humble fare, what we might pick up at the supermarket on a weekday evening, he could become a tangible human being, a figure with whom one could identify. He came alive in the degree to which he partook in everyday activities, in so far as he wept and had messy affairs, bit his nails and was jealous of his friends, liked honey but reviled marmalade – anything to melt the stony heroism of the official statue.

...

Nevertheless, an assumption remained that only the great were fit fodder for biographies.

A couple of centuries before, a dissenting voice had briefly shattered this puzzling unanimity, only then to be ignored amidst the growing mountain of biographies amassing over it’s owners grave. That voice had belonged to Dr Johnson, and it had mused that, ‘There has rarely passed a life of which a judicious and faithful narrative would not be useful. For, not only has every man great numbers in the same condition with himself, to whom his mistakes and miscarriages, escapes and expedients, would be of immediate and apparent use; but there is such a uniformity in the state of man, considered apart from decorations and disguises, that there is scarce any possibility of good or ill, but is common to human kind’ ...

What biography disguised, in its concern for unusual lives, was the extraordinariness of any life ...

In dwelling on the actions of those we can never share drinks with, biographies shield us from our universal involvement, explicit or not, in biographical projects. Every acquaintance requires us to understand a life, a process in which the conventions of biography play a privileged role. Its narrative traditions govern the course of the stories we may tell ourselves about those we meet, it shapes our perceptions of their anecdotes, the criteria according to which we arrange their divorces and holidays, the way we select, as if the choice were natural, certain of their memories but not others.

... [I]t suggested that there was no reason why the next person to walk into my life should warrant less than the empathetic effort one could expect from the most banal of biographers. It seemed that unusual value might lie in exploring the hidden role of biographical convention in our most ubiquitous but complex pastime – understanding other people.